Alchemy and the Transgendering of Mercury M. E. Warlick

Abstract: Within late medieval alchemical texts, Latin authors adopted both classical and Arabic concepts of physical matter. They assumed that metals were composed of two polarized substances - hot, dry and masculine Philosophic Sulphur, and cool, wet and feminine Philosophic Mercury - whose 'Chemical Wedding' within the laboratory produced the Philosophers' Stone.

As visual illustrations developed in alchemical manuscripts and early printed books from the late fourteenth century onward, artists represented these substances with a variety of male and female characters, with Philosophic Mercury almost always depicted as a woman. At the same time, the planet Mercury, which oversaw the ripening of the metal Quicksilver within the earth, also played an important role within alchemical illustrations. This paper will examine how artists navigated this confusion by examining gendered images of the philosophical concept Mercury, the metal Mercury, and the planet Mercury, in light of shifting attitudes towards women in early modern science.

Alchemists use the term Mercury in many ways, including references to the planet Mercury, to the metal mercury, to the god Mercury, and, perhaps most importantly, to the concept of 'Philosophic Mercury'. Alchemical artists derived their images from astrological, religious and mythological visual precedents, although some alchemical images were truly innovative in their representations of alchemical substances and laboratory processes. These broader visual traditions influenced alchemical artists, who adapted their images of Mercury to the various kinds of Mercury they found in alchemical texts. This paper will investigate the complexity and contradictions surrounding representations of Mercury in alchemical imagery.

It will trace the evolution of different visual representations of Mercury and examine the ways in which alchemical artists negotiated the gender differences between them. These observations are drawn from a larger study of images of women, gender and sexuality in alchemical manuscripts and early printed books. As alchemical imagery developed from the late fourteenth through the early seventeenth centuries, the transformations between these differing representations of Mercury reveal shifting attitudes towards gender both within alchemical philosophy and beyond.

Alchemical theories of physical matter descend from the Greeks, who described physical matter as consisting of the four elements of earth, water, air and fire with their shared oppositional qualities of cold, wet, hot and dry. In his Meterologica, Aristotle explained the formation of metals and minerals within the earth from 'exhalations', one vaporous and one smoky.1

Dry exhalations produce infusible minerals and stones that are dug or quarried. Aristotle gave the examples of sulphur, realgar, ochre and ruddle, another red pigment. He also placed the composite ore cinnabar in this category. On the other hand, he explained that fusible metals are formed by moist vaporous exhalations, providing the examples of iron, gold and copper, which are mined. In the appended fourth chapter of the Meterologica, now ascribed to pseudo-Avicenna, the author explained the opposing qualities of substances by setting up a list of binary oppositions, both active and passive, that determine the ways in which the four qualities of cold or heat, moisture or dryness produce change in substances.2

As Greek theories migrated through the Arab world, a shift based on these teachings occurred, in which the cool, wet qualities of physical substances became more strongly contrasted to the hot, dry qualities, and these eventually polarized into the two philosophical concepts of Mercury and Sulphur. In Arab alchemical texts, the theory evolved that hot, dry, masculine Sulphur and cool, moist, feminine Mercury were the two component parts of all metals.3

Alchemical texts often reiterate that these terms were not to be confused with the actual substances of sulphur and mercury, but rather they were conceptual properties of physical matter.

In later alchemical illustrations, Philosophic Sulphur and Philosophic Mercury become the two main characters in alchemical narratives and they appear in a variety of male and female figural representations.

The relationship between alchemy and the seven planets visible to the naked eye also stems from ancient origins.4 Each planet, including the Moon and the Sun, rules over the production of a metal within the earth in a continuing ripening process that evolves from lead to gold. The alchemist's task is to learn how to duplicate and quicken these natural processes. Lead is considered to be the least pure of all the metals, and thus it is ruled by Saturn, the slowest and outermost visible planet.

The Moon and the Sun rule over the most refined metals of silver and gold. While early texts fluctuate somewhat in drawing relationships between the other planets and their metals, Mars was typically connected with iron, Jupiter with tin, and Venus with copper. The planet Mercury first ruled over electron, an alloy of silver and gold, but later came to be linked to the metal mercury, or quicksilver.

The metal mercury was well known in the ancient world.5 Theophrastus described a simple technique to obtain mercury by crushing cinnabar ore (HgS), mercuric sulphide, a naturally occurring combination of sulphur and mercury. Over time, techniques were developed to produce vermillion, a synthetic version of cinnabar and a brilliant red pigment valued by painters.6 Laboratory operations to separate mercury from cinnabar or to produce vermillion bear interesting parallels to descriptions of alchemical processes.

While these artisan practices may have contributed to the development of alchemy's philosophical theories, alchemical philosophy drew from many other sources as well. Suffice it to say that the metal mercury does have quite curious properties, being the only metal that is liquid at room temperature and that has the ability to create alloys with most common metals, including silver and gold, but not iron. It was used in ancient times to colour other metals in amalgam gilding, and this may have influenced its reputation as an agent of transformation.

By the time that alchemy returned to the Latin West via twelfth century translations of Arabic texts, references to Philosophic Mercury, the planet Mercury and the substance mercury were common. In fact, Philosophic Mercury had been elevated to play a significant role in alchemical operations. The Latin author Geber, now identified as a Franciscan monk named Paul of Taranto, postulated a 'Mercury alone' theory, developed from the Sulphur-Mercury theory of the Arabs.7 While accepting classical form/matter polarities, several late medieval alchemical texts asserted that masculine Sulphur played a crucial, but relatively minor role, while Mercury contained all that was necessary for the successful completion of the work.

This view is expressed in another text, the Liber secretorum alchimie:

All strength and operation rests upon mercury, it being the mother and matter of all metals, just as hyle is the first cause ... The material cause comes about through congealing as in the first hyle, the mother of all creatures, as established by the Supreme Artisan.8

This text was written in I 257 by Constantine of Pisa, a medical student who was collecting his university lecture notes on the natural sciences, including aspects of alchemical philosophy and practice.9

Two versions of this manuscript have survived and both contain illustrations. 10 The Glasgow version was written in Germany in 1361.

The Vienna version is a late fourteenth century Flemish adaptation of Constantine's text entitled, The Secrets of My Lady Alchemy.

Illustrations in early alchemical manuscripts were rare with the exception of vessels and pointy fingers in the margins. The Glasgow manuscript contains relatively simple cosmological diagrams that are largely unfinished. The Vienna manuscript embellished its diagrams with figural elements, and thus became the first alchemical manuscripts to do so. Throughout the text, Constantine explains the relationship between theological, cosmological and 'alchemical principles. The more elaborate illustrations in the Vienna manuscript represent the planets, their metals, the zodiac, and the creation of heaven and earth, drawing on Genesis. In two panels (Fig. 1 ), overlapping circles contain personifications of the planets in their medieval appearances, inscribed with the names of the planets and the metals they rule.11

At the top left, the hand of God begins an unfolding cycle of creation. Below his hand is a crowned personification of the cosmos, followed by the planets Saturn, Jupiter, Mars and the Sun. The following folio continues with Venus, Mercury, Luna, the Earth, and the animals of the air, land and sea.

The personifications of Jupiter and Venus are both regal, although their typical metals are reversed here, with Jupiter ruling copper and Venus ruling tin.

Saturn is a three-headed personification of Time ruling lead, while Mars is a soldier, ruling iron.

Fig. 1. Creation of the planets, metals and animals, Constantine of Pisa, The Book of the Secrets of Alchemy, ca. 1380, paper; ONB Vienna: Cod. 2372, fols. 46v, 47r; reproduced by kind permission of the Osterreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

The next panel represents the planet Mercury as a bishop in the second circle from the top (Fig. 1, right). Jean Seznec charted the persistence of astrological personifications throughout the Middle Ages, demonstrating that they never really disappeared during the Christian era, but that their appearances certainly changed from Greco-Roman representations.12

The curious representation of Mercury as a bishop extends back to the Babylonian god Nebo, who was a scholar. During a transitional period when astrological manuscripts were returning to the Latin west, artists often had only written descriptions of classical gods and goddesses rather than actual visual reputations.

In some cases, Arabic artists had adapted western classical deities to representations of their own gods, or they had given them local attributes, as where Hercules wields a scimitar rather than a club. 13 Thus medieval artists merged Middle Eastern representations of the scholarly scribe god Nebo into a western clerical scholar surrounded by books, and then into a bishop. An alchemical manuscript at Cambridge depicts the planet Mercury as a bishop marrying the masculine Sun and the feminine Moon.14

The planet's proximity in the sky to the Sun may have sparked Mercury's representation as an intermediary between them. Later there would be many alchemical representations of the so-called 'Chemical Wedding' of the Sun and Moon, but the appearance of the planet Mercury as a bishop is an early construct that would soon disappear. Planetary influence over the generation of metals within the earth and over laboratory processes will continue in alchemical texts long into the early modern period.

In the early fifteenth century, two new alchemical manuscripts appeared with abundant allegorical imagery.15 Both would serve as models for much of the alchemical imagery that developed in later manuscripts and early printed books. A German Franciscan monk named Ulmannus produced the Buch der Heiligen Dreifaltigkeit (Book of the Holy Trinity) while he was attending the Council of Constance, 1414-1418.

Written in the midst of strong religious debate and controversy, this manuscript weaves together alchemical theory and practical laboratory recipes within a matrix of religious and political allusions, delivered with the fervour born of a belief in the imminent threat of the Antichrist.

Within the text, correspondences are drawn between the metals, the planets, virtues and vices.16 The point is often made that Christ and Mary are unified, as Sulphur and Mercury are joined together in physical matter. At the end of the manuscript, the Crowning of Mary by the Trinity of Father, Son and Holy Spirit represents the feminine perfection of Philosophic Mercury. Christ's crucifixion and resurrection represents masculine perfection and the production of gold.

The other early fifteenth century manuscript is the Aurora Consurgens (Rising Dawn), of which the oldest version is in Zurich. Within the text, Sulphur and Mercury are presented as personifications of the Sun and the Moon in a variety of interactions. In one illustration, the male Sun is a knight jousting with his feminine opponent, the female Moon.17

They ride on a Lion and a Griffin, symbols of masculine fixity and feminine volatility. Their shields contain small symbols of their opponents - he has the Moon, she has the Sun - as both Sulphur and Mercury were thought to each contain a small part of each other's essence.

In another illumination from the same manuscript the two characters tie the legs of a dragon, representing the primal matter, the base material from which the two substances are purified into silver and gold. Primal matter must first be destroyed, as the volatility of Mercury is fixed, before further operations can continue. This manuscript also contains sexually explicit scenes of the couple's sexual union, drawing on the Song of Songs, and its romantic tale of a lover and his beloved, interpreted here as an allegory of chemical fusion in the laboratory.

Both manuscripts, the Book of the Holy Trinity and Rising Dawn, reflect philosophical and religious ideas of late medieval alchemical texts. Both contain many prominent images of women, influenced by the 'Mercury alone' theory. The late Gothic period saw the celebration of the cult of the Virgin Mary in abundant religious imagery.

The alchemical emphasis on feminine Mercury is thus expressed in a variety of religious images of women within these early manuscripts, including the Virgin Mary, Eve, a female serpent and the Black Bride of the Song of Songs, in addition to the Moon. Both manuscripts also contain images of the alchemical androgyne, a half-male/half-female figural symbol of the Philosophers' Stone, the child of the union of Sulphur and Mercury, and this dual figure will prove to be one of the most enduring alchemical symbols.

Later copies and adaptations of both manuscripts were produced into the mid-sixteenth century. Some developed the romance of Sulphur and Mercury even further, including the Rosarium philosophorum and Donum Dei series.18 Artists adapted images from the Book of the Holy Trinity and the Rising Dawn in these newer illustrations. ln one image, a woman, identified as 'Philosophic Mercury', stands on two fountains flowing beneath her feet. In the Glasgow version the fountains are labelled with glyphs for the Sun/gold and the Moon/silver (Fig. 2).19

She is nude to represent her purity. Her long loose golden hair represents her virginity, conveying a more secular representation of the virgin mother of the Philosophers' Stone. She holds a chalice of healing in her left hand and an encircling serpent in her right, objects held by earlier androgynous figures in the Book of the Holy Trinity. This image again reinforces the late medieval idea of the 'Mercury alone' theory, in which feminine Mercury contains all that is necessary for the completion of the work.

With the advent of printing, several compilations of earlier alchemical texts appeared, at first without illustrations. In 1550, an illustrated version of the Rosarium Philosophorum was printed with an illustrated title page and a narrative series of twenty woodcuts. The woodcuts are accompanied by a German poem, 'Sol und Luna,' whose author has not been identified."

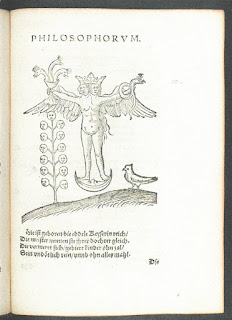

The artist adapted again images from the Book of the Holy Trinity and the Rising Dawn into this new series that begins with the meeting, romance and sexual union of the Sun King and Moon Queen. The two figures then fuse into a half-male/half-female androgyne within a sarcophagus. Evaporation and condensation within the vessel are represented by a small male figure rising to the top and returning after a rain shower. The perfection of the feminine is achieved half way through the series, and is represented by an androgyne standing on a crescent Moon, to indicate the production of silver (Fig. 3).

A second and more volatile conjunction follows, this time with a small female figure rising and descending after the rain. At the end of the series, the royal androgyne stands triumphantly over a three-headed serpent, beside a tree with thirteen heads of the Sun. The final images of the Crowning of Mary and the Resurrection of Christ indicate the perfection of both Mercury and Sulphur.

Fig. 2. Philosophic Mercury, Spruch der Philosophien (Rosarium Philosophorum series), German, late sixteenth century, paper; University of Glasgow Library, Sp. Coll. Ferguson Ms. 6, Fol. 164v; reproduced by kind permission of the Special Collections Department of the University of Glasgow Library, Glasgow.

Within this series, the image of the androgyne on the Moon (Fig. 3) plays a similar role to the representation of 'Philosophic Mercury' (Fig. 2).

Fig. 3. Alchemical Androgyne, De alchimia opuscula, Part II: Rosarium Philosophorum, Frankfurt: Cyriacus Jacob, 1550, woodcut; University of Glasgow Library, Sp. Coll. Ferguson Al-y.18, fig. 10; reproduced by kind permission of the Special Collections Department of the University of Glasgow Library, Glasgow.

It would be inaccurate to say that such an evolution of the gendered imagery is strictly chronological, especially since the Glasgow drawing of female 'Philosophic Mercury' was created later than the woodcut, and both are based on earlier models. There are similarities in the objects held in the hands while the wings on the fountains of the Sun and the Moon are now attached to the androgyne. Although the androgyne is both male and female, its text indicates the perfection of the feminine has been achieved through an imperial birth (an Empress). The Moon is emphasized by a tree containing thirteen faces of the moon, in addition to the crescent moon on which the androgyne stands.

By the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Renaissance had inspired new transformations of the alchemical Mercury, depicted as a god in his Greco-Roman attire with winged hat and heels, and a caduceus entwined with two serpents (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Mercury and the Androgyne, Daniel Stolcius, Chymisches Lustgartlein, Frankfurt: Lucas Jennis, 1624, engraving by Baltazar Schwan; University of Glasgow Library, Sp. Coll. SM 1000, fig. LXIX; reproduced by kind permission of the Special Collections Department of the University of Glasgow Library, Glasgow.

Several factors influenced the return and appearance of this Mercury. One was the rise in the reputation of the Egyptian philosopher Hermes Trismegistus, a character whose reputation had evolved throughout the Middle Ages." Hermes' fame as an ancient philosopher ranked him in some circles even higher than Plato and Aristotle. His role as the most important Hermetic philosopher secured his position as the founding father of alchemy. In 1488, soon after the appearance of Ficino's printed version of the Corpus Hermeticum, an image of Hermes Trismegistus, attributed to Giovanni di Stefano, was inserted into the mosaic pavement of the Siena Cathedral.r' In alchemical texts, the ancient philosopher Hermes was often merged with the Greek god Hermes, and this would influence the role that the god Hermes/Mercury would begin to assume in alchemical imagery.

The second important person to shift the spotlight towards the classical god Mercury was the irascible Doctor Paracelsus, who lived in the early sixteenth century. His theories on alchemical medicine, or iatrochemisty, were especially influential. Paracelsus postulated a number of revisions to prevailing alchemical theory, but for the purpose of this paper, the most important was his shift from the duality of the Mercury-Sulphur theory to one that included Salt as a third essential component of physical matter.

This trinity was not entirely new to alchemy as it paralleled other Trinitarian views, such as body, soul and spirit. 23 However, because of the emphasis that Paracelsus placed on three, rather than two, essential parts of primal matter, Salt became an equal partner to continuing representations of Philosophic Sulphur and Philosophic Mercury. For Paracelsus, Salt is the body or the physicality of matter, the ash left after a substance had been burned, Mercury was the volatile spirit of matter or escaping gases, and Sulphur became its soul, the essence that is collected.

The male god Mercury thus comes to represent Salt, the physical body that binds together male Sulphur and female Mercury. His caduceus encapsulates this notion, with its two serpents entwined on a single staff (Fig. 4). This engraving appeared first in J. D. Mylius's Philosophia Reformata of 1622, one of several images in this text containing the god Mercury, now fully attired in his classical garb. 24

He represents not onlyTrismegistus, a character whose reputation had evolved throughout the Middle Ages." Hermes' fame as an ancient philosopher ranked him in some circles even higher than Plato and Aristotle. His role as the most important Hermetic philosopher secured his position as the founding father of alchemy.

In 1488, soon after the appearance of Ficino's printed version of the Corpus Hermeticum, an image of Hermes Trismegistus, attributed to Giovanni di Stefano, was inserted into the mosaic pavement of the Siena Cathedral.r' In alchemical texts, the ancient philosopher Hermes was often merged with the Greek god Hermes, and this would influence the role that the god Hermes/Mercury would begin to assume in alchemical imagery.

The second important person to shift the spotlight towards the classical the Hermetic wisdom that is necessary for completing the work, but he also functions as a guardian watching over the alchemical androgyne resting in the garden. Elsewhere in Mylius's book, the seven ancient planets with their traditional classical attributes are placed within a cavern to oversee the creation of their metals within the womb of the earth. Daniel Stolcius reprinted many of these illustrations in his Chymisches Lustgartlein of 1624. The rising importance of Hermes Trismegistus and of Paracelsus within alchemical philosophy is suggested by the inclusion of both men on

Stolcius's title page.

One the most important alchemical texts published in the early seventeenth century was Michael Maier's Atalanta Fugiens, which also god Mercury. Maier was well versed in alchemical philosophy. He wrote several texts that interpreted ancient myths and legends 26 as alchemical allegories. The publisher J. T. De Bry probably engraved the images, although they have also been attributed to Mattaeus Merian. Whoever the artist, he was well versed in the artistic currents of the day, and had access to imagery from earlier alchemical manuscripts, upon which many newer illustrations were based.

Mythological and gendered transformations took place within this Renaissance humanist environment, often inspired by Ovid's The struggle described above between the knightly Sun, the feminine Moon and the Dragon in the Aurora Consurgens, is transformed in Emblem XXV of Atalanta Fugiens into a mythological Metamorphosis. scene, in which 27 Apollo (Phoebus), god of the Sun, and Diana (Cynthia), goddess of the Moon, use the club of Hercules to destroy the dragon. In the distance, 24 the celestial brother and sister are depicted in their mythic roles as archers. In Emblem XXXVIII, the winged god Hermes is represented in a passionate embrace with the goddess Aphrodite (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Emblem XXXVIII. Hermes/Mercury, Aphrodite, Eros, and the Hermaphrodite, Michael Maier, Atalanta Fugiens, Oppenheim: J. T. De Bry, 1618, engraving; University of Glasgow Library, Sp Coll Ferg Euing Bd 16.g-6, p. 161; reproduced by kind permission of the Special Collections Department ofthe University of Glasgow Library, Glasgow.

According to the Ovidian myth their child was a boy, Hermaphroditus, who later merged with the nymph Salmacis in a pool, to become a single figure of both sexes, the Hermaphrodite. In the motto of this image, Hermes/Mercury becomes the Father of the androgynous child and AphroditeNenus its mother, as the alchemical allegory is retold, this time as a classical myth.28

Thus is happens that feminine Philosophic Mercury, mother of the alchemical androgyne and the Philosopher's Stone, becomes the masculine god Mercury, father of the Hermaphrodite. As feminine Mercury becomes masculine Mercury, the wider context of the increasing masculinization of early modern science seems to be a factor influencing these changes within alchemical imagery.

More visual examples can be found, but it seems sufficient here to propose that gender is a most interesting filter to use when examining the evolution of alchemical imagery.

Alchemy was a science of transformation, and its illustrations demonstrate just how mercurial those transformations could be.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου